FIRST EDITION 2008 150 PAGES 9"x12" HARDCOVER BLACK AND WHITE + COLOR PHOTOGRAPHY: all film ISBN: 97880981900612

Beauty of the Fight is John Urbano's first book and documentary.

Both the book and the documentary entitled Beauty of the Fight grew out of photographer and director John Urbano’s discovery of Barraza and El Chorrillo, the very neighborhood in Panama that U.S. military invaded and razed to the ground to capture General Manuel Noriega in 1989. What began for Urbano as a photography expedition into the resulting red zone soon turned into a filmmaking endeavor the momentum of which, in turn, has resulted in the expeditious release of this book. In fact, he never let up snapping stills while he was documenting stories, and both color and black and white photographs play a prominent role in the film.

Children stand out bigger than life in the book perhaps because they most strikingly contrast the broken neighborhood of Barraza and El Chorrillo. They look like children anywhere in the world—innocent, unaware of possibly easier (or more difficult) worlds elsewhere. Whether at play or trying to comprehend the loss of a house or the inexplicable presence of a Norte Americano with a camera, these children are unaware of the so-called “Kodak moment” so often spoken of in the U.S. They are pure and natural thus wholly present in these images.

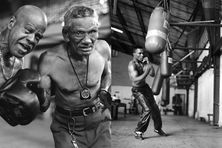

The same holds true for the adult world in these shots. However, grownups in Barraza and El Chorrillo have experienced war, violence, hunger, displacement, poor health, and limited education, and are therefore anything but innocent in the sense of having experienced the vicissitudes of life. What the photographer seeks to capture in his adult subjects is the enduring love, hope, and hard work of a people who believe they can make their world better. The boxer training for the world championship has his people’s dreams written in every sinew of his body. The fight for dignity is what the shots ultimately reveal in the people of this rundown neighborhood.

Such close proximity to photographic subjects doesn’t come without risk. Danger, whether apparent or not, is behind every image. Warring gangs rule the streets and keep a vigilant eye out for any stranger who steps foot on their turf. But John’s disarming style gained him entry into even the gang-banger’s world. In front of the camera, gang members almost satirize themselves, shooting with their fingers, bulging their tattoos, smoking with sophisticated defiance. If gang members seem to have about them a residue of childlike innocence, every one of them has death entwined in his fingers in the form of a knife or gun. Bullet hole scars are a common feature on the gang-banger’s body.

In places most frequented by cats and rats, we see that people can be natural in broken settings as well as in the clipped and trimmed “sets” of industrialized nations (possibly more so). There’s beauty in the earthy pastels, the festive decorations, the chaos of rites and rituals. A shantytown, corrugated tin roofs and all, is its own visually intriguing microcosm. Trash has its own aesthetic.

We see here wonderful use of the found object: the fading photograph on a wall, a tape measure hanging from the tailor’s chair (in the film), the business hours hand-painted in the corner of a barber’s window—shots reminiscent of a Neruda ode. Walls tell stories, communicating people’s pasts, territories, and deaths. History lives in jewelry looted during the invasion. People don’t possess much, so photos, mementos, and everyday objects take on greater physical power and value.

The photographer probes every direction in his art: action silhouettes in black and white, colors one can almost smell, patterns of mundanity in high-rises, the championship ring upon the once-upon-a-time world champion’s finger. Hands often find their way into his frames. Astonishing spaces and shapes of unexpected sky suggest a world beyond which the eye might escape. Light appears in the corner of a frame just when shadow overwhelms. There are contrasts of human beauty and debris, black and white photos juxtaposed with color, linkages of kids behind wire mesh and a rooster in his cage.

Images range from low income block housing to the many hand-carved wooden houses of the canal construction era, from the orderly and silent graves to the Black Christ palanquin pulsing upon the male community’s shoulders, but these shots are also about what isn’t evident on the surface. Why have so many houses been razed to the ground? Why do children and adults peek furtively through gaps in boards? What’s the story behind their faces? What forces of history are upon them?

Like the child on the book cover and in the film poster, Urbano’s images bring into question the nature of innocence. They drive home the idea that the fight to survive is as natural as eating or sleeping. Only in Beauty of the Fight, the struggle’s clear and true to life.